|

|

|

September/October

1999 Issue

Nature

on Display

Southwest Florida’s environment is fully appreciated

at Calusa Nature Center

St.

Petersburg, Florida, residents Evan Yates and his mother have been busy

nonstop while visiting Sanibel and Captiva for several days, but 3-year-old

Evan is in the mood for a change. My 11-year-old daughter and I think

of a perfect place to take them after Evan’s nap: Calusa Nature Center

and Planetarium in Ft. Myers.

Now

in its 27th year, the private, nonprofit nature center offers visitors

an education in the natural environment of Southwest Florida. Its museum,

Audubon aviary, Indian village, trails, and planetarium are run by four

full-time naturalists, a director, and an assistant director. Many interns

also work there throughout the year. The facility sits on 105 acres of

pine flatwoods on the east side of Ft. Myers. Now

in its 27th year, the private, nonprofit nature center offers visitors

an education in the natural environment of Southwest Florida. Its museum,

Audubon aviary, Indian village, trails, and planetarium are run by four

full-time naturalists, a director, and an assistant director. Many interns

also work there throughout the year. The facility sits on 105 acres of

pine flatwoods on the east side of Ft. Myers.

Front-desk volunteer Barbara Bacon hands us a nature

center trail guide. She asks us to return the helpful guides, which describe

nature center buildings, show trails and their lengths, and identify trees

and other plants.

The nature center also sponsors a wide variety of programs

such as preschool story hours, night hikes, laser light shows, summer

camps, and television meteorologists discussing Southwest Florida’s

summer flooding, lightning, and hurricanes. During the school year, the

nature center’s full-time naturalists do outreach programs on the

birds of prey or reptiles of Florida.

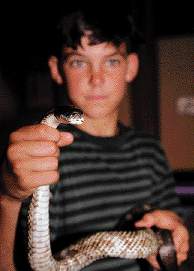

Visitors

generally go through the nature center on their own but can pay extra

for guided walks. Naturalists do animal presentations twice a day, usually

with a baby alligator or crocodile and nonpoisonous snakes. The planetarium

offers daily shows. Naturalist Jill Evans runs the astronomy shows using

21 slide projectors inside the planetarium’s 40-foot dome. She says

plans are in the works for updating to video and laser discs. Admission

to the planetarium is extra.

As we enter the museum, it’s hard to know where

to begin. We gravitate toward a tank with freshwater pond life, including

turtles and a baby alligator about 18 inches long. A nearby tank houses

a baby crocodile, which is about the same size. Helpful signs explain

the differences between the two, noting that the crocodile has a long,

skinny snout, is grayish green, and its upper and lower teeth stick out

when its mouth is shut.

A table holds a book giving tips on “mosquito-proofing

your yard.” A huge enclosed beehive, called “Dance of the Bees,”

gives a fascinating view of a bee’s life. The Chilean rose-haired

tarantula looks rather frightening, but it is described as being “fairly

harmless.” A chest with pullout trays holds countless specimens of

beautiful butterflies. Nearby, Evan doesn’t want to stop playing

with a wooden sea-life puzzle.

The

snake exhibit is fascinating and its glass cages include a red rat snake,

an Eastern diamondback rattler, and a venomous dusky pygmy rattler. Visitors

can touch the many snakeskins that have been shed. A black, red, and yellow

Eastern coral snake looks as if it could be plastic. A venomous cottonmouth

is all curled up, and a sign on the Florida kingsnake cage notes that

it eats other snakes.

We wander onto the museum’s outdoor back deck,

which has a fossilized half of a baleen whale skull that was found on

Ft. Myers Beach. Nearby is a manatee skeleton. There are also rows and

rows of cages full of mice, which are fed to the snakes, small alligators,

and small birds of prey. A sign explains that starting with one pair of

mice, if all future generations would survive and continue to breed, would

produce 15,000 mice in one year.

Just outside the museum are two big alligators housed

in a fenced area. A gopher tortoise sits in safety on the other side of

the fence. Evan, meanwhile, is captivated by huge, colorful butterflies

that are painted on the outside of the museum

It’s

not a far walk to the large aviary, whose inhabitants are permanently

injured. Summer intern Rhonda Roth, from the University of Wisconsin,

is inside one of the cages, getting ready to feed the birds. “These

are raptors, which are big birds of prey that have powerful talons,”

she tells us. “The bald eagle’s talons exert a thousand pounds

of pressure. We also have vultures, which technically are not in the raptor

group. See how that turkey vulture has a red head like a turkey?”

Most of the birds have had wing amputations. A red-tailed

hawk has a feather deformity, which nature center staffers think was possibly

caused by poisoning. A big, beautiful female bald eagle is missing a wing,

but no one knows why.

Naturalist Laura Wewerka, who has worked at the nature

center since 1992, says that because the birds are unable to hunt on their

own, feeding time consists of giving them dead rats. The rats are covered

with a yellow stain, which is from liquid vitamins.

The center buys the dead rats, as well as some dead

mice, from a Gainesville, Florida, company called Gourmet Rodent. “The

mice are for our snakes, which do have a cushy life,” says Wewerka.

“We’re pretty protective of them. The mice are already dead

when we give them to the snakes, so the snakes won’t get bitten.”

“Bad birdy!” shouts Evan as the bald eagle

begins to eat a dead rat.

Near the aviary is a caged area for a bobcat that was undernourished as

a kitten and has a hip deformity. Wild bobcats roam the property, but

the caged cat is unable to run and thus is a permanent resident.

A bit farther down the path is the Indian village, comprised

of chickees, thatched structures built by Seminole Indians. Nearby, several

large posters tell the story of the Calusa Indians, the nature center’s

namesake tribe who lived in Southwest Florida from about 900 AD to 1700

AD.

It’s getting near dinnertime for everybody. As

we walk back toward the museum, we see Roth feeding the alligators. She

throws a dead pigeon to one, and the alligator lunges at it so fiercely

that we instinctively jump back a bit. “It is scary when it’s

thrown to them, isn’t it?” Roth asks, while the ’gator

drags its dinner into the water.

As if anticipating our next question, Roth notes: “We

feed them whatever is thawed out for the day, be it pigeons, fish, turkey

necks. But we can’t stress enough how people must never feed alligators.

When that happens, whenever they see people, they think food.”

Calusa Nature Center is home to more than 50 animals.

Keeping all of them fed and healthy is quite expensive, so the center

appeals to visitors and the community to become “adoptive parents”

and donate money to help care for the animals.

Most of the funding for the nature center comes from

admission charges, membership fees, grants, and fund-raising. A big fund-raiser

is its Halloween Walk, held annually on the grounds during the last week

and a half of October. Many of the exhibits also have local sponsors.

The nature center is about to close for the day and

we have a quick look around the museum gift shop. In addition to books,

stationery, and jewelry, it sells birdseed, honey from LaBelle, a wooden

kit for making a model tarantula, and the ever-popular Sanibel-Captiva

Nature Calendar.

Roth walks by, this time carrying a strange-looking

iguana on her shoulder. “He’s Guac, short for Guacamole, and

it’s a sad story,” she says. “Most of our animals never

get named because they’re still wild and not pets. But Guac is our

pet and we don’t put him on display.” Guac’s twisted body

and patches of flaking skin are signs that he didn’t get enough calcium

when he was young, says Roth. “Guac is a good example for people

thinking of keeping an exotic pet. If you’re going to do it, make

sure you do a lot of research.”

For information on the Calusa Nature Center and Planetarium,

call 941/275-3435 or log on to its Web site at www.calusanature.com. Admission

is $4 over the age of 12, $2.50 for ages 3-12, and free under 3. Hours

are Monday through Saturday, 9 a.m. to 5 p.m., and Sunday, 11 a.m. to

5 p.m. 275-3435. 3450 Ortiz Avenue, near the intersection of Colonial

Boulevard, and Six Mile Cypress Parkway in Ft. Myers.

By Libby

Grimm

|